The Sahara Desert, often perceived as an unlivable domain, was once the cradle of the Garamantian Empire. This ancient civilization flourished by exploiting concealed aquifers, though their imprudent consumption of these water reserves eventually led to their downfall—underscoring the vital necessity of responsible groundwater management.

In an environment marked by scant rainfall and exceedingly high temperatures, the Sahara is commonly considered one of Earth’s most unforgiving habitats. While the Sahara has seen periods of more favorable climatic conditions, a civilization similar to today’s climate managed to develop techniques to harness water from its seemingly barren terrain, prospering until the aquifers were exhausted.

Table of Contents

Recent Insights into the Garamantian Civilization

Fresh scholarly work, disclosed at the Geological Society of America’s GSA Connects 2023 conference, delves into how a combination of fortuitous environmental conditions enabled the Garamantian Empire to utilize hidden underground water reserves. This sustained the empire for almost a thousand years before the groundwater sources were entirely depleted.

Frank Schwartz, a professor at the School of Earth Sciences at Ohio State University and the lead researcher of the study, noted, “Civilizations ascend and descend according to the dictates of the natural environment, whereby specific geographical and climatic features can permit or inhibit human growth.”

Transition from Verdant Terrain to Arid Expanse

Between 11,000 and 5,000 years ago, monsoonal rains transformed the Sahara into a relatively lush landscape, supplying surface water and creating hospitable conditions for societies to flourish. However, the ceasing of the monsoons around 5,000 years ago led the Sahara to revert to its desert state, causing civilizations to withdraw—except for a notable exception.

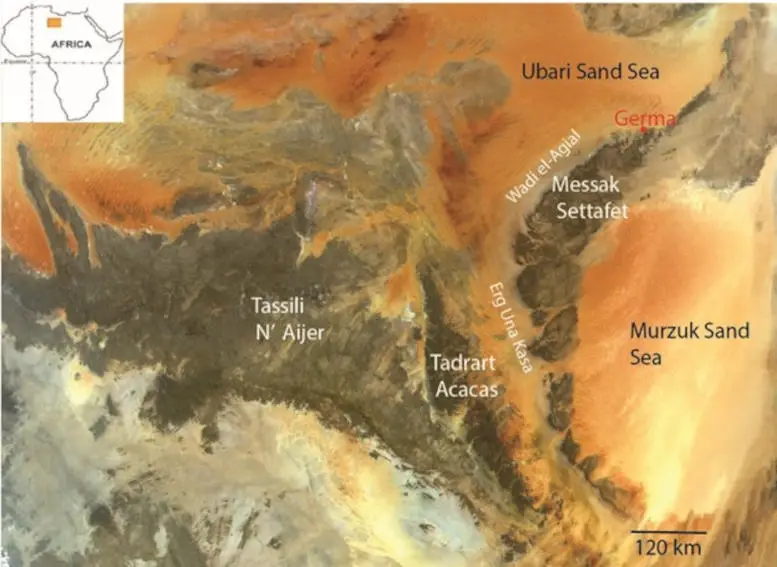

The Garamantes existed in the southwestern Libyan desert from 400 BCE to 400 CE, experiencing hyper-arid conditions nearly identical to the current ones. They became the first highly organized society to establish themselves in a desert devoid of a perennial river. While the surface water bodies of the Sahara’s greener epoch had disappeared by the time the Garamantes came into existence, fortuitously, an extensive sandstone aquifer lay underground, potentially one of the world’s largest according to Schwartz.

Techniques in Groundwater Harvesting

The technology for groundwater extraction was imported through camel trade routes from Persia, using systems known as foggara or qanats. This involved the construction of a slightly inclined underground tunnel, reaching just beneath the water table, allowing the groundwater to flow down into irrigation channels. The Garamantes constructed an estimated 750 kilometers of subterranean tunnels and vertical access shafts, primarily between 100 BCE and 100 CE.

Interpreting Garamantian Hydrogeology

Schwartz combines earlier archaeological data with hydrological analyses to comprehend how the local geology, topography, and specific runoff and recharge circumstances created the optimal hydrogeological conditions for the Garamantes to extract groundwater.

“Contrary to qanats in Persia that are recharged annually by snowmelt, the conditions here had no such recharge,” Schwartz remarked.

The Garamantes were beneficiaries of environmental serendipity, including a previous wet climate, suitable topography, and special groundwater conditions. Their good fortune terminated when groundwater levels fell below the foggara tunnels.

Contemporary Concerns and Implications

Schwartz points out two troubling trends: the increasing prevalence of extreme environments globally, such as in Iran, and the growing tendency to unsustainably exploit groundwater reserves.

“Even in modern instances like California’s San Joaquin Valley, groundwater is being consumed faster than its rate of replenishment,” Schwartz asserts. “Although California recently experienced a wet winter, it came after two decades of drought. Should the inclination for drier conditions persist, California may eventually face the same predicament as the Garamantians.”

With no new influx of water to replenish the aquifers and no available surface water, the Garamantian civilization eventually collapsed. Their story serves as a poignant warning about the potential perils of unsustainable groundwater utilization.

Reference: “Survival in Harsh Landscapes: Hydrological Luck and the Rise and Fall of the Garamantian Empire in the Sahara” by Frank Schwartz, Motomu Ibaraki, and Ganming Liu, published on 16 October 2023 in GSA Connects 2023.

DOI: 10.1130/abs/2023AM-391971

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Garamantian Empire

What is the primary focus of the article?

The primary focus of the article is the Garamantian Empire, an ancient civilization that thrived in the Sahara Desert by tapping into hidden groundwater reserves. The article explores their rise and eventual decline, emphasizing the importance of sustainable groundwater management.

Who was Frank Schwartz and what was his role in the research?

Frank Schwartz is a professor in the School of Earth Sciences at Ohio State University. He was the lead researcher in the study that explored the environmental and hydrological conditions that allowed the Garamantian Empire to flourish and ultimately decline.

How did the Garamantes manage to thrive in the Sahara Desert?

The Garamantes thrived by harnessing groundwater using technology known as foggara or qanats, which involved constructing slightly inclined underground tunnels just beneath the water table. This allowed groundwater to flow down into their irrigation systems.

What led to the downfall of the Garamantian Empire?

The downfall of the Garamantian Empire was primarily due to the unsustainable extraction of groundwater. When groundwater levels fell below the tunnels they had constructed for extraction, the empire eventually collapsed due to lack of water.

What modern-day parallels does the article draw concerning groundwater management?

The article draws parallels with contemporary challenges like California’s San Joaquin Valley, where groundwater is being used up at a rate faster than it’s being replenished. The article serves as a warning about the risks of unsustainable groundwater usage.

What were the unique environmental conditions that favored the Garamantian civilization?

The Garamantes benefited from a combination of environmental factors, including a previously wetter climate, suitable topography, and special groundwater settings that made it possible to extract water using foggara technology.

What are the key lessons to be learned from the Garamantian Empire?

The key lesson to be learned is the critical importance of sustainable groundwater management. Their story serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the potential perils of overutilizing water resources.

What are the broader implications of the article?

The broader implications of the article concern the increasing prevalence of extreme environments globally and the growing tendency to unsustainably exploit groundwater reserves. It serves as a cautionary tale for modern societies.

More about Garamantian Empire

- Geological Society of America’s GSA Connects 2023 Conference

- Ohio State University School of Earth Sciences

- Hydrological Analysis Techniques

- Groundwater Management Best Practices

- History of the Sahara Desert

- California’s San Joaquin Valley Groundwater Crisis

- Sustainable Water Resource Management

5 comments

Wow, never knew the Sahara had such a rich history. Makes you think twice bout how we’re using our water resources today, huh?

Incredible to think that a civilization thrived in such harsh conditions. the Garamantes must’ve been some kind of genius in water management. But all good things come to an end I guess.

Fascinating! Schwartz and his team must’ve done some deep digging, no pun intended, to bring all this info to light. Can’t ignore the lessons here.

Really opens your eyes about the urgency of sustainable water use. California could learn a thing or two from this. History has a way of repeating itself, doesn’t it?

Groundwater isn’t infinite, who would’ve thought? Seriously though, we need to step up our game in resource management, or we’re next in line after the Garamantes.