Image credit: A surviving fragment of Denisova 11 (known as Denny) bone found in the Denisova Cave in Russia, attributed to a female born to a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Source: Institute for Basic Science

A recent paper in the esteemed journal Science by a global collaboration of researchers demonstrates that historic variations in atmospheric CO2 levels, which subsequently led to changes in climate and flora, played a crucial role in determining the timing and geographical locations where early human species engaged in interbreeding.

It is recognized that contemporary humans carry a minor fraction of DNA derived from other hominin species, namely Neanderthals and the lesser-known Denisovans.

In the year 2018, scientists publicly declared the discovery of a person they later named Denny, who existed 90,000 years ago and was identified as the offspring of a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother [Slon et al. 2018]. Denny, along with other mixed-heritage individuals found in the Denisova Cave, attests to the likelihood that intermingling was not solely a feature of Homo sapiens but was prevalent among other hominin species as well.

Typically, to understand the timing and locations of such human hybridization events, researchers have depended on the paleo-genomic analysis of exceptionally rare fossil samples and their even less abundant ancient DNA content. However, in this Science article, the team—composed of climate scientists and paleo-biologists from South Korea and Italy—took an alternative methodology. Utilizing extant paleo-anthropological evidence, genetic datasets, and advanced computer simulations of past climatic conditions, they ascertained that Neanderthals and Denisovans exhibited different environmental predilections. Specifically, Denisovans were considerably more adapted to cold climates, typified by boreal forests and even tundras, in contrast to Neanderthals who favored temperate forests and grasslands.

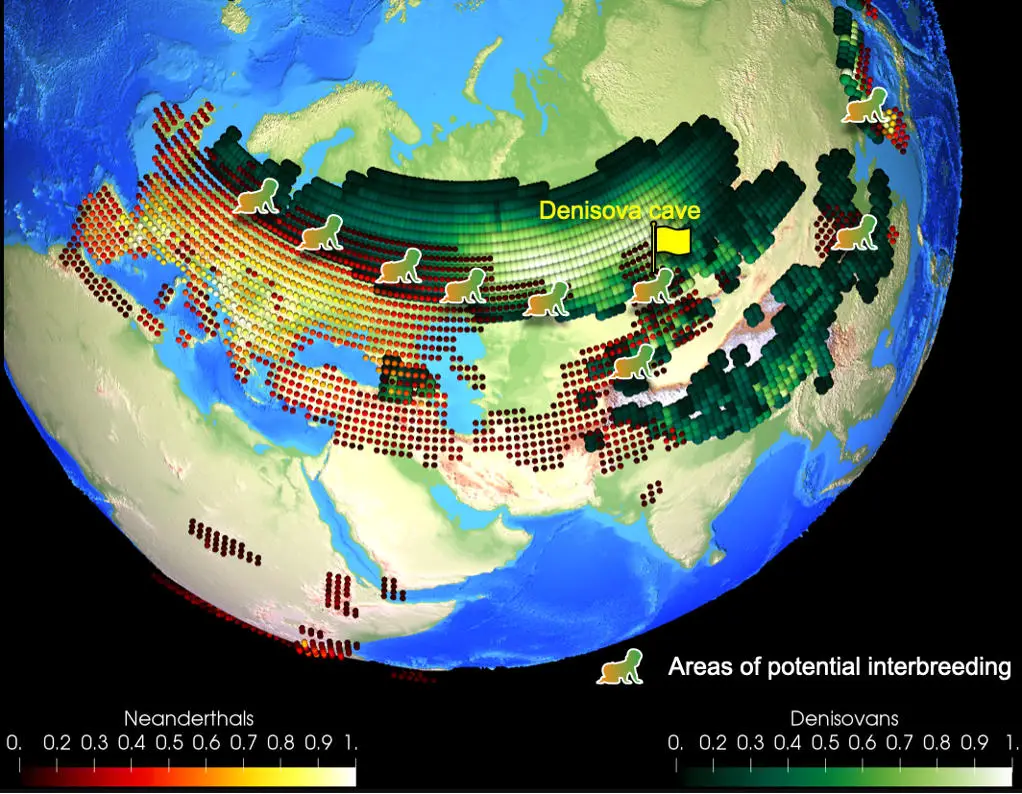

Image credit: Depiction of preferred habitats for Neanderthals (in redscale) and Denisovans (in greenscale). Overlapping regions in Central Asia and Northern Europe where interbreeding might have occurred are indicated. Source: Institute for Basic Science

Dr. Jiaoyang Ruan, a postdoctoral researcher at the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP), South Korea and the principal author of the study, states, “This implies that their preferred habitats were geographically segregated, with Neanderthals primarily found in southwestern Eurasia and Denisovans in the northeast.”

Their comprehensive computer models revealed that during warm interglacial periods, wherein Earth’s orbital path around the Sun became more elliptical and northern hemisphere summers occurred when closer to the Sun, the habitats of these hominin species started to geographically overlap. Prof. Axel Timmermann, the corresponding author of the study and director of the ICCP, notes, “When these habitats converged, it facilitated increased interactions among these groups, thus augmenting the likelihood of interbreeding.”

This simulation aligns not only with the known history of the first-generation Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid, Denny, but also corroborates other instances of interbreeding around 78,000 and 120,000 years ago. Future paleo-genetic studies could validate the newly proposed supercomputer-based models that predict potential interbreeding episodes around 210,000 and 320,000 years ago.

To further comprehend the climate-related factors affecting this east-west interbreeding dynamic, the researchers scrutinized how vegetation configurations have altered across Eurasia in the past 400,000 years. Their findings indicate that increased levels of atmospheric CO2 and mild interglacial climates led to the eastward expansion of temperate forests into central Eurasia, thereby opening migratory pathways for Neanderthals into Denisovan territories. Dr. Ruan comments, “It appears that climatic fluctuations between glacial and interglacial periods set the stage for a long-lasting and unique tale of human interconnection, the genetic footprints of which are still discernible today.”

A major hurdle in this study involved estimating the favored climatic conditions for Denisovans. Prof. Pasquale Raia from the University of Naples, Federico II in Italy, a co-author, says, “Given the scant Denisovan data, we had to develop new statistical methodologies that could also account for acknowledged ancestral relations among human species. For the first time, we could approximate locations where Denisovans might have resided, and we found that apart from regions in Russia and China, northern Europe could also have been hospitable to them.”

As for whether Denisovans ever ventured west of the Altai Mountains remains speculative; however, this question could be answered through extensive genetic studies focusing on Denisovan lineage in European populations. Such future work is anticipated to offer new insights into the complex interplay between early human dispersal, habitat invasion, and genetic diversification.

Reference: “Climate shifts orchestrated hominin interbreeding events across Eurasia” by Jiaoyang Ruan, Axel Timmermann, Pasquale Raia, Kyung-Sook Yun, Elke Zeller, Alessandro Mondanaro, Mirko Di Febbraro, Danielle Lemmon, Silvia Castiglione, and Marina Melchionna, published on 10 August 2023 in Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.add4459

Table of Contents

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Hominin Interbreeding and Climate Change

What is the primary focus of the article?

The article primarily focuses on a study published in the journal Science that investigates the role of climate change and fluctuating atmospheric CO2 levels in influencing the interbreeding of early human species, specifically Neanderthals and Denisovans.

What methodology did the researchers use to study interbreeding among early human species?

The researchers used an alternative approach that involved a blend of extant paleo-anthropological evidence, genetic datasets, and advanced computer simulations of past climatic conditions. This approach was used to understand the environmental preferences of Neanderthals and Denisovans and how climate changes influenced their opportunities for interbreeding.

What new insights does the study offer about Neanderthals and Denisovans?

The study suggests that Neanderthals and Denisovans had different environmental preferences. Denisovans were more adapted to cold climates, characterized by boreal forests and tundra, whereas Neanderthals favored temperate forests and grasslands. These differing environmental preferences were revealed through advanced computer simulations.

How did climate change affect the likelihood of interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans?

According to the computer simulations in the study, during warm interglacial periods, the habitats preferred by Neanderthals and Denisovans began to overlap geographically. This overlap increased the chances for encounters and interactions, thereby raising the likelihood of interbreeding between the two species.

What are the implications of this study for our understanding of human evolution?

The study adds a new dimension to our understanding of human evolution by suggesting that climatic conditions played a significant role in shaping early human interbreeding patterns. It indicates that shifts in climate and vegetation could have opened pathways for genetic mixing among different hominin species.

Who were the main researchers involved in the study?

The main researchers involved in the study were Dr. Jiaoyang Ruan, a postdoctoral researcher at the IBS Center for Climate Physics in South Korea, and Prof. Axel Timmermann, the director of the ICCP and professor at Pusan National University. They were supported by a team of climate scientists and paleo-biologists from South Korea and Italy.

What challenges did the researchers face in this study?

One of the key challenges was estimating the preferred climatic conditions for Denisovans, given the sparse data available. The researchers had to develop new statistical tools to account for known ancestral relationships among human species for this purpose.

When was this study published and where can it be accessed?

The study was published on 10 August 2023 in the journal Science. The article includes a DOI reference for those interested in accessing the original research paper.

More about Hominin Interbreeding and Climate Change

- Original Science Journal Article

- Institute for Basic Science

- IBS Center for Climate Physics

- Pusan National University

- University of Naples, Federico II

- Paleogenomics Explained

- Overview of Hominin Evolution

- Climate Change and Human Evolution

- Neanderthal and Denisovan Genomics

6 comments

Wow, this is groundbreaking stuff. Never thought climate change could’ve played such a key role in early human interaction. Mindblowing really.

They had me at Denisovans and Neanderthals. Always a sucker for prehistoric mysteries. But honestly, who thought CO2 levels would come into play?

This just makes me wonder, what other kinds of interactions between early human species are yet to be discovered? Can’t wait to read more on this.

i’m fascinated by how they used computer simulations. Science is amazing, isn’t it? Puts a whole new spin on human history.

This is not just about history, but about understanding our own DNA. The past informs the present in ways we can’t even imagine. Makes me wanna delve deeper into anthropology!

A study like this really shows the importance of interdisciplinary research. Climate science, biology, anthropology—all coming together. just amazing.